The Four Disconnections

The problems of our Modern existence are a result of our profound disconnection from the relationships that sustain us

"The great tragedy of our time is that we're all looking somewhere else for connection, when our belonging is right here, in our bodies, with each other, with the earth beneath our feet, and in the great mysterious beauty that holds it all together." — Robin Wall Kimmerer

I have this beautiful memory from a couple of years ago. It was a late September morning, and I was on one of our “barefoot forest walks” with my then 7-year-old son. Rain had fallen overnight, and the moss yielded like a sponge beneath his small feet. He stopped suddenly, crouching to examine something I couldn't see from where I stood. "Dad!" he called, his voice vibrating with excitement. "Come quick! It's breathing!"

I made my way over, expecting to find a small animal. Instead, he pointed to a fallen log covered in bright orange fungi. He placed his small hand gently on the surface. "Can you feel it? The whole forest is breathing."

I knelt beside him and placed my palm on the log. The forest was indeed breathing—not just the subtle exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide, but a palpable aliveness that I had learned not to notice (or that, in my age, I had forgotten). My son hadn't yet been taught to ignore this connection, to see himself as separate from the living world around him. In that moment, I glimpsed what we all once knew: that we exist within a web of relationship so intimate and constant that we could no more separate from it than separate from our own heartbeat.

This memory returns to me often as I consider how we've arrived at our current moment of ecological and social crisis. The symptoms are everywhere: climate destabilization, biodiversity collapse, social polarization, epidemics of loneliness and mental distress. But beneath these symptoms lies something more fundamental—a profound disconnection from the relationships that sustain us.

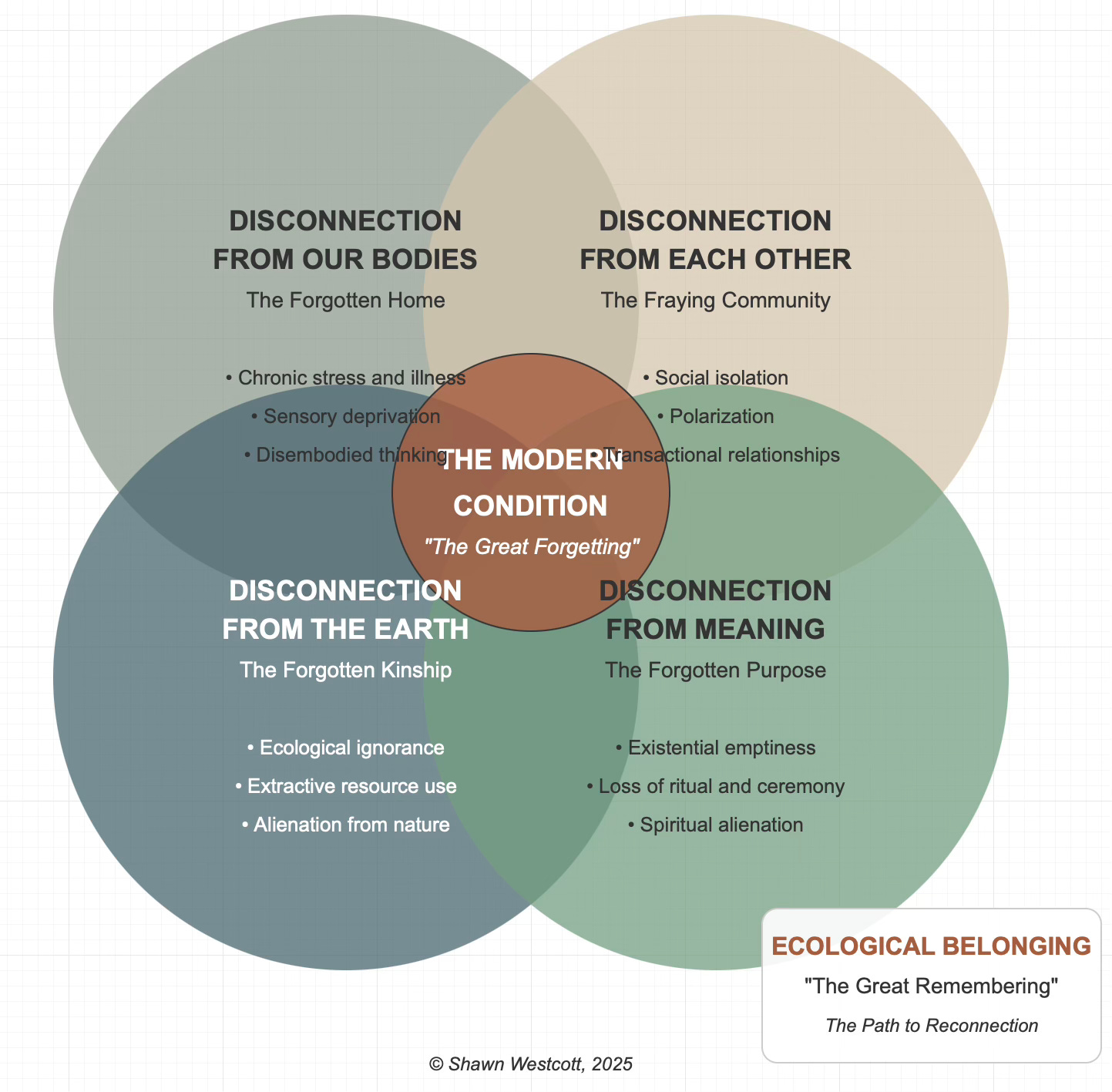

This disconnection isn't just one problem among many. It's the underlying pattern that manifests in what I call the “Four Disconnections” — four distinct but interrelated dimensions: our disconnection from our bodies, from each other, from the Earth, and from deeper meaning. Understanding these four disconnections can help us see more clearly how we collectively lost our way and, more importantly, how we might find our way back.

Disconnection from Our Bodies (The Forgotten Home)

Think of the last time you were fully present in your body—not analyzing, planning, or judging, but simply experiencing the sensation of being alive in this moment. For many of us, these moments have become rare islands in a sea of disembodiment.

From our earliest education, we're trained to privilege mental activity over physical sensation. We learn to override our body's signals of hunger, fatigue, or emotional distress in service of productivity and performance. Our screens pull our attention into virtual realms while our bodies sit forgotten, waiting for us to return.

Prior to my own healing process, this disconnection was so clear. I'd been having back pain for months, but I kept pushing through. One day, I suddenly couldn't move. As I lay there waiting for help, I realized I couldn't remember the last time I'd actually felt my body before the pain became unbearable. It was like I'd been living from the neck up for years.

This disconnection from our embodied experience isn't just uncomfortable—it fundamentally distorts our relationship with reality. Our bodies are our primary instruments for perceiving and responding to the world. When we lose touch with bodily sensation, we lose access to essential information and wisdom.

Consider how many decisions you've regretted because you ignored that subtle feeling in your gut. Or how often you've pushed beyond your natural limits because you didn't notice the early signals of depletion. Our bodies know things our conscious minds haven't yet registered, but we've been conditioned to override these signals rather than honor them.

This disconnection from embodied wisdom creates suffering on multiple levels. Physically, it contributes to chronic stress, disrupted sleep, digestive issues, and immune dysfunction. Emotionally, it leaves us unable to process and integrate our experiences, creating patterns of reactivity or numbness. Socially, it impairs our ability to sense others' emotional states and respond with empathy. Spiritually, it cuts us off from the direct experience of being alive in this moment—the foundation of genuine presence.

We see the consequences everywhere: in our healthcare systems overwhelmed by preventable lifestyle diseases, in our addiction to substances that temporarily numb disconnection's pain, in our endless pursuit of physical perfection rather than embodied wisdom. The body, treated as object rather than subject, becomes another resource to optimize and control rather than a source of innate intelligence.

Yet within this disconnection lies the seed of reconnection. Your body has been waiting for you to return, with its amazing capacity to regulate, heal, and guide when given the chance. Later, we'll explore practical ways to rebuild this primary relationship. For now, simply notice: How does it feel to be in your body as you read these words? What sensations arise? What happens when you bring kind attention to these sensations without trying to change them?

This simple act of returning awareness to embodied experience begins the journey back to wholeness.

Disconnection from Each Other (The Fraying Community)

Humans evolved as intensely social creatures. For most of our existence, we lived in small bands where everyone knew each other by name, where multiple generations shared daily life, where survival depended on cooperation and reciprocity. Our brains and nervous systems developed in this context of continuous connection.

Today, many of us live in a paradoxical state of crowded isolation. We may be surrounded by more people than ever, yet genuine connection has become increasingly rare. The average American moves homes 11.7 times in their lifetime, repeatedly severing geographic community ties. (My number is moves is embarrassingly above average.) Many of us live far from extended family, in single-generation households. Digital technologies create the illusion of connection while often deepening our isolation.

I had a conversation with an old family friend, a retired teacher from a small town in Pennsylvania, who described to me watching his community transform over decades. He talked about how, when he was growing up, if your car broke down, you knew the names of a dozen neighbors who would help. Now people live there for years without knowing who lives next door. When his wife died, he realized he had no one to call who lived within fifty miles.

This disconnection from human community isn't merely sad—it's physically harmful. Research consistently shows that social isolation increases risk of premature death by 26-32%, making it more dangerous than obesity or air pollution. Loneliness elevates stress hormones, increases inflammation, and suppresses immune function. We are literally dying from disconnection.

The consequences extend beyond individual suffering. When we don't know our neighbors, we lose the informal support systems that have traditionally sustained communities through difficult times. Problems that could be solved through mutual aid become crises requiring institutional intervention. Trust erodes, polarization increases, and we become more vulnerable to exploitation and manipulation.

This disconnection manifests in our built environment: neighborhoods designed for cars rather than pedestrian interaction, public spaces converted to commercial venues, zoning laws that separate where we live, work, learn, and play. It shapes our economy: transactional relationships replacing reciprocal ones, job mobility valued over community stability, care work systematically undervalued. It alters our politics: abstract ideological affiliations replacing face-to-face governance, polarization flourishing in the absence of genuine relationship.

The very concept of a "self-made" individual—someone who succeeds through pure individual effort—epitomizes this disconnection. No human has ever been self-made. We enter the world utterly dependent on others and remain interdependent throughout our lives, relying on countless people we'll never meet for our food, shelter, education, and infrastructure. Yet this myth of radical independence continues to shape our economic and social systems.

Despite these powerful forces of disconnection, our longing for genuine community persists. We see it in the spontaneous support networks that emerge after disasters, in intentional communities experimenting with new-old ways of living together, in neighborhood initiatives reclaiming public space for connection. The capacity for deep relationship remains within us, waiting to be remembered and rekindled.

Disconnection from the Earth (The Forgotten Kinship)

For most of human history, people understood themselves as participants in a living, animate world, intimately connected to particular landscapes and their non-human inhabitants. Every aspect of life—from food procurement to sacred practice—unfolded in conscious relationship with the more-than-human world.

Today, many of us live in human-dominated environments where direct contact with other species and natural processes has been systematically minimized. The average American child spends just 4-7 minutes in unstructured outdoor play daily, compared to over 7 hours with electronic media. Many adults spend 90% of their lives indoors, experiencing nature primarily through screens or as scenery glimpsed through windows.

When we experience ourselves as separate from natural systems rather than embedded within them, we make decisions that damage these systems without recognizing that we are damaging ourselves.

One of the participants in a workshop I was running for Ecological Belonging grew up on a farm in Ukraine but now lives in Washington, DC. She told me about how, when growing up they knew when to plant by watching the swallows return. She realized she had been in Amsterdam for six months without knowing the name of a single local bird or plant. She felt like a ghost, “floating above the land rather than living within it.”

This physical separation has profound psychological and spiritual consequences. We suffer from what Richard Louv calls "nature-deficit disorder"—a constellation of symptoms including attention difficulties, emotional dysregulation, and diminished sensory awareness resulting from inadequate contact with natural environments. Studies consistently show that time in nature reduces stress, improves cognitive function, and enhances emotional wellbeing—benefits we forfeit through disconnection.

Beyond these individual impacts, ecological disconnection fundamentally distorts our understanding of reality. When we experience ourselves as separate from natural systems rather than embedded within them, we make decisions that damage these systems without recognizing that we are damaging ourselves. We treat air, water, soil, and biodiversity as externalities to economic calculation rather than the foundations of all wealth. We pursue growth patterns that undermine the very conditions required for life to flourish.

This disconnection pervades our language, which sorts the world into "natural" and "human" as mutually exclusive categories. It shapes our ethics, which often extends moral consideration only to human interests. It informs our spirituality, which frequently places the divine beyond the earth rather than within it. It structures our economics, which treats living systems as "resources" to be extracted rather than communities to which we belong.

The consequences surround us: in climate systems destabilized by carbon emissions, in oceans filled with plastic, in rapidly accelerating extinction rates, in forests converted to monocultures. These are not separate crises but interconnected manifestations of a single underlying pattern: our forgotten kinship with the living Earth.

Yet this forgetting isn't complete. Even in the most artificial environments, plants push through cracks in concrete, reminding us of life's persistence. Children still experience wonder at their first encounter with a butterfly or the ocean's vastness. Our bodies still respond to circadian rhythms, seasonal shifts, and weather patterns. The capacity for ecological relationship remains within us, waiting to be reawakened.

Disconnection from Meaning (The Forgotten Purpose)

Humans naturally seek meaning beyond mere survival—some understanding of our place in the larger story of existence, some purpose that transcends our individual lives. Traditionally, this meaning emerged through cultural and spiritual frameworks that situated personal experience within larger patterns of significance.

Many of us now live in what philosopher Charles Taylor calls a "disenchanted" world—one where material explanations have replaced sacred understanding, where efficiency and productivity trump purpose and meaning, where the question "how" dominates while "why" receives diminishing attention. We inhabit what poet T.S. Eliot called "the wasteland," a landscape spiritually barren despite material abundance.

When I was growing up, my aunt, Terry, who is a hospice nurse, would tell me about the disconnection she saw in her patients. "So many people reach the end of their lives and wonder what it was all for. They've achieved everything society told them to want—career success, material comfort, even family—but something essential is missing. They lived disconnected from any purpose greater than themselves."

This disconnection from deeper meaning manifests in various ways: in the "diseases of despair" (addiction, depression, suicide) that plague even materially wealthy societies; in the endless consumption that temporarily fills the void where purpose should be; in the cynicism that dismisses any values beyond self-interest; in the anxiety that haunts achievement without meaning.

Modern systems often exacerbate this disconnection. Educational institutions focus on marketable skills rather than wisdom or purpose. Workplaces reward productivity over meaningful contribution. Media bombards us with superficial concerns while deeper questions receive fleeting attention. Even religious institutions sometimes reduce spirituality to doctrine or morality rather than direct engagement with life's fundamental mysteries.

The consequences extend beyond individual suffering. Without a sense of meaning that transcends self-interest, we struggle to make sacrifices for future generations or distant others. Without stories that connect us to something larger than ourselves, we become vulnerable to nihilism or fundamentalism. Without practices that nurture wonder and reverence, we lose touch with the sacred dimension of existence that has guided human communities throughout history.

Perhaps most fundamentally, disconnection from meaning leaves us without adequate frameworks for navigating death, suffering, and impermanence. When life's difficulties arrive—as they inevitably do—we lack the spiritual resources to integrate these experiences into a meaningful whole. We find ourselves, as author Viktor Frankl observed, suffering without meaning, which is the definition of despair.

Yet even amid this disconnection, the human hunger for meaning persists. We see it in young people's passionate engagement with environmental and social justice, in the resurgence of interest in contemplative practices, in new forms of community organized around shared values and vision. The capacity for meaning-making remains within us, waiting to be reclaimed and renewed.

“When you wake up and you see that the Earth is not just the environment, the Earth is us, you touch the nature of interbeing.”

―Thich Nhat Hanh, Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet

The Interconnected Nature of Disconnection

These four disconnections—from body, community, earth, and meaning—do not exist in isolation. They form an interconnected pattern, each reinforcing and perpetuating the others.

When we disconnect from our bodies, we lose access to the empathy that connects us to others and to the sensory experiences that connect us to the earth. Our capacity for meaning diminishes when we cannot feel the depth and richness of embodied existence.

When we disconnect from community, we lose the relationships that help us maintain embodied wisdom, the collective capacity to care for our shared landscapes, and the traditions that transmit meaning across generations.

When we disconnect from the earth, we damage the physical foundation of embodied health, undermine the ecological systems that support human community, and lose touch with the natural cycles that have always informed our understanding of meaning and purpose.

When we disconnect from meaning, we lack the spiritual frameworks that honor the body's wisdom, the values that prioritize community over individual gain, and the reverence that motivates ecological care.

This interconnected pattern of disconnection helps explain why single-issue approaches often fall short. We cannot address climate change without also healing our relationship with our bodies, our communities, and our sense of meaning. We cannot solve the loneliness epidemic without reconnecting with embodied wisdom, ecological relationship, and purposeful existence. True healing must address all four dimensions of disconnection simultaneously.

Yet the interconnected nature of disconnection also reveals an encouraging truth: reconnection in any dimension positively influences the others. When you restore embodied awareness, you naturally become more attuned to others, more sensitive to ecological relationships, more receptive to meaning. When you rebuild community ties, you create conditions that support embodied health, collective environmental care, and shared purpose. Each step toward reconnection ripples outward, strengthening the entire web of relationship.

The Journey Back to Connection

Understanding these four disconnections provides a map for the journey back to wholeness. Like someone lost in the wilderness who finally recognizes where they are, we can now orient ourselves and begin moving in the direction of home.

The disconnections we've explored aren't simply the result of modern technology or industrial society—these are symptoms, not causes. Every human culture has grappled with the tendency toward forgetting our fundamental interconnectedness. What's unique about our moment is the scale and pervasiveness of disconnection, not its existence.

Nor is this journey about rejecting the genuine benefits of modern developments. Technology, science, global communication, and material innovation all offer valuable tools when placed in service of reconnection rather than further separation.

Instead, this journey involves a remembering in the deepest sense—not just mental recollection but literally re-membering, putting the members back together, restoring the relationships that constitute our full humanity. It's about reconnecting with capacities we've always possessed but temporarily forgotten how to access.

In other essays I have explored practical pathways back to connection in each dimension:

How to return to embodied wisdom through practices that restore trust in your body's intelligence

How to rebuild meaningful community in an age of isolation and mobility

How to reawaken ecological relationship through direct experience of the more-than-human world

How to reclaim sources of meaning that transcend individual achievement and consumption

These pathways aren't separate but intertwining, each strengthening the others. Together, they offer a holistic approach to healing the disconnections at the root of our personal and collective challenges.

The journey begins with awareness—simply noticing the disconnections in your own experience without judgment or despair. Where do you feel separated from your body's wisdom? From meaningful community? From the living Earth? From a sense of purpose larger than yourself? This honest recognition creates the possibility for change.

Reflection and Mapping Your Own Disconnections

Having gone through this work myself, I thought it would be valuable to help you reflect on your own four disconnections and how they manifest in your own life. You might consider the following:

Body: When do you feel most connected to your body's wisdom? When do you feel most disconnected? What practices or circumstances support your embodied awareness? What patterns or habits pull you into disembodiment?

Community: Who truly knows you? Where do you experience authentic belonging? What obstacles prevent deeper connection with others? What forms of community do you long for but currently lack?

Earth: What is your relationship with the natural world where you live? Do you know the plants, animals, weather patterns, and landforms of your home place? Where do you experience yourself as part of nature rather than separate from it? What prevents more frequent connection with the more-than-human world?

Meaning: What gives your life purpose beyond survival and comfort? When do you experience a sense of belonging to something larger than yourself? What practices connect you with the deeper dimensions of existence? Where do you sense a hunger for greater meaning?

This reflection isn't about adding self-judgment to your burdens. None of us chose the disconnected culture we were born into. Rather, it's about honestly assessing your starting point for the journey back to connection. Only by acknowledging where we are can we begin moving toward where we wish to be.

I return to that moment in the Swedish forest with my son. His innocent perception of the forest's breath reminds me that reconnection isn't about acquiring something new but about returning to something we've always known.

The disconnections we've explored run deep, shaped by centuries of cultural development and reinforced by powerful systems. Yet the capacity for reconnection remains alive within us—in our bodies that still respond to circadian rhythms, in our nervous systems designed for co-regulation with others, in our senses that awaken in the presence of natural beauty, in our spirits that hunger for meaning beyond consumption.

The journey back to connection begins with a simple but profound shift: from seeing ourselves as separate individuals to recognizing ourselves as interconnected participants in the living world. From this recognition, new possibilities emerge—not just for personal healing but for cultural and ecological renewal.